Dear Damien,

I must have had your paper on Moses ages ago, made my notes in the margin but never shared my understanding of the man’s early life with you.

Used the following to gainsay those who called him and the Exodus “a myth”.

It would appear we differ on both dynasties and chronology – isn’t the XII too early?

MOSES was a general, as fully described by Josephus in Antiquities, Book II, ch X.

In ch XI, after he had virtually saved Egypt as its victorious general over the Ethiopians/Cushites, he had to flee for his life from an assassination plot. He was heir to a throne in Egypt as the ruler had a daughter but no grandchildren. Josephus: “if Moses had been slain, there was no one, either a kin or adopted, that had any oracle on his side for pretending to the crown of Egypt.” Here are our clues – a dynasty in which Moses is General, and one which effectively ended at the point in history that Moses fled and did not regain authority in the land. There is such a dynasty which also exercised jurisdiction in the Northeastern Delta where Israel dwelt and Moses was found – Dynasty XIII.

The total length of this dynasty according to Africanus’ and Eusebius’ epitomes from Manetho was 453 years under 60 rulers. But the version of Barbarus provides a missing detail from Manetho. It reveals that for a time the court was not only at Thebes, but at Bubastis in the Delta for the first 153 years (Alfred Schoene’s edition of Eusebius, p. 214).

In the Turin Canon catalogue of kings of the thirteenth dynasty, listed number 17, is “The General” with the throne name of Semenkhkare (Gardiner’s Egypt of the Pharaohs, p. 440; and Weigall’s History of the Pharaohs, pp 136, 151-152). The Egyptian word for “the General” was Mermeshoi – not in all dynastic history does this title appear again as the personal name of a ruler of Egypt.

When Moses was made General or Commander of the Troops, he automatically inherited royal authority, as only kings could have the supreme command of the army, explaining his appearance in the list. Before the rise to power of this famous General, the thirteenth dynasty was of Asiatic blood. Its kings at time bore the epithet “the Asiatic” – hence no basic prejudice in adopting the Hebrew child Moses into the family. (See volume II, ch II of the revised Cambridge Ancient History, ed.1962.)

The sixteenth king listed in the Turin Canon – just before “the General” – is Userkare Khendjer – the latter being an un-Egyptian personal name. He ruled over the Delta as well as Upper Egypt. A pyramid of his has been found at South Saqqara. No descendant of his is known to have succeeded to the throne. Though nothing more is known of this man’s family, every evidence points to him as the Pharaoh whose daughter is mentioned in the book of Exodus. Within a few years the influence of this dynasty in the eastern Delta ceased.

The kings of this obscure period often have their names associated with king Neferkare (Turin Canon) on royal seals who is Phiops of Manetho, and commonly known as Pepi the Great. Here is the final proof that these minor rulers of Dynasty XIII were contemporaneous with the last great Pharaoh of the sixth dynasty of Memphis – the pharaoh of the Oppression. More than one name on a scarab has puzzled many historians, who view Egypt as generally ruled by one king at a time, but literally hundreds of such seals have been found. They are generally treated with discreet silence, for the implication of these seals would revolutionise the history of Egypt. (See The Sceptre of Egypt, by William C Hayes,, Vol.I, p.342)

Moses is finally able to return to Egypt “and it came to pass in the course of those many days that the king of Egypt died” (Ex. 2:23) confirms that it was a long wait as Pepi the Great ruled for 94 years and died at age 100, succeeded by his son Menthesuphis (Manetho) or Merenre II-Antyemzaef (Turin Canon) – the Pharaoh of the Exodus who ruled only one year 1487-1486, perishing in the Red Sea.

His widow Nitocris (Manetho) or Nitokerty (Turin Canon) ruled 12 years, followed by their son Neferka “the younger” – his first born elder brother and heir presumptive having died at the time of the Exodus.

Manetho ends his list here as the invading Hyksos having by then taken full control of the country with their Dynasty XV and ruled Egypt for the next 400 years.

I feel we are on safe ground to designate Pepi the Great as the oppressive pharaoh. Userkare Kendjer with an ethnic affinity with the Hebrews does not strictly apply the rules emanating from Memphis by elevating Moses who must later have gained huge popularity following his military success. Those factors may well have raised serious concerns at Memphis HO, prompting Pepi the Great to seek Moses’ death by giving those assassination orders to the Bubastis court, and also maintaining his fatwa against Moses till the end of his life and reign.

Best regards

….

Damien Mackey replies:

Dear Dick

I just remembered that I, a few months ago, wrote a proposed synthesis of the biblical era, from Abraham to the Exodus, with the corresponding Egyptian history (and archaeology). See my:

The article still has to be finished, but it already contains the basis of what my view is. Fundamental to my reconstruction are the following (after that I am tentative):

-The archaeological period from Abram at the time of the four Mesopotamian kings, to the Exodus, is bookended by Abram in Late Chalcolithic and Ghassul IV (Transjordan) and the Exodus Israelites as the Middle Bronze I (MBI) people.

-According to this archaeological evidence, Abram was contemporaneous with pharaoh Narmer, who may even have been the Pharaoh of Abram and Sarai. This latter, the biblical Abimelech pharaoh of Abraham and Isaac, was clearly a very long-reigning ruler, which would suit pharaoh Aha, the first dynastic king (who may have been Narmer, and Menes).

-Joseph is surely Imhotep, and Ptah-hotep.

-I fully accept the expert testimony of Dr R. Cohen (Israelites as MBI) and Professor Emmanuel Anati (Har Karkom is Mount Sinai).

-Anati notes (and I accept this) that the story of the Egyptian Sinuhe shares ‘a common matrix’ with that of Moses fleeing Egypt for Midian. (Obviously there are some vast differences as well between these two tales). That nails Moses to Late Amenemes I and early Sesostris I. Revisionists have found some striking 12th dynasty correlations with the Exodus account (e.g. those bricks mixed with straw).

-The MBI people do just what the Israelites did in their trek through the Paran desert, Transjordania and into Palestine, where Early Bronze Jericho falls.

The 13thdynasty may possibly be partly contemporaneous with the life of Moses.

But be careful. The name, “Moses”, did not mean “General”. It was given to Moses with the meaning of being “drawn from the water” (Exodus 2:10): “She named him Moses, saying, “I drew him out of the water”.” So that might shake your correspondence between Mermoshis and Userkare K.

(Perhaps Joseph, not Moses, was more likely to have left a dynasty of Asiatics).

You will see that I, too, have the 6th dynasty contemporaneous with the era of Moses, though I have not yet been able fully to integrate it all. Given my synthesis of dynasties (following Courville’s clue but not his model), then some 13th dynasty princes (or whatever they were) may well have been contemporaneous with the 6th dynasty’s Neferkare (Pepi the Great).

But Pepi the Great was not a founder, a “new king” (exodus 1:8), so you perhaps need to allow for two major pharaohs before the Pharaoh of the Oppression: namely, the founder Pharaoh and then, as according to the Artapanus tradition, the “Chenephres”(Neferkare?) who married Moses’ Egyptian ‘mother’, “Merris” (Meresankh, or Meres-ankh).

Artapanus’s“Chenephres” (Neferkare) and “Merris” pattern is fulfilled both with Chephren and Ankhesenmerire (i.e. Meresankh), in the 4th dynasty, and perhaps with Huni (Neferkare) and Meresankh, as explained in the above article, in relation to Sneferu (as Moses).

Merenre, followed by Nitocris, then the Hyksos, is a pattern that I, too, have previously proposed for the finale – but without properly having been able to blend the entire 6th dynasty with the biblical picture.

I hope that this is helpful

Damien.

An Ancient Earthquake

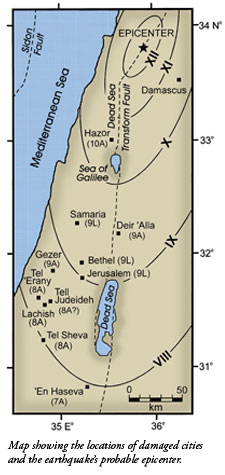

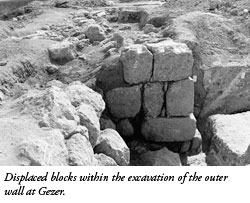

An Ancient Earthquake  The epicenter was clearly north of present-day Israel, as indicated by the southward decrease in degree of damage at archaeological sites in Israel and Jordan. The epicenter was likely in Lebanon on the plate boundary called the Dead Sea transform fault. A large area of the ancient kingdoms of Israel and Judah was shaken to inflict "general damage" to well-built structures (what is called Modified Mercalli Intensity 9 or higher). The distance from the epicenter (north of Israel) to the region of "significant damage" to well-built structures (what is called Modified Mercalli Intensity 8 that is south of Israel) was at least 175 kilometers, but could have been as much as 300 kilometers.

The epicenter was clearly north of present-day Israel, as indicated by the southward decrease in degree of damage at archaeological sites in Israel and Jordan. The epicenter was likely in Lebanon on the plate boundary called the Dead Sea transform fault. A large area of the ancient kingdoms of Israel and Judah was shaken to inflict "general damage" to well-built structures (what is called Modified Mercalli Intensity 9 or higher). The distance from the epicenter (north of Israel) to the region of "significant damage" to well-built structures (what is called Modified Mercalli Intensity 8 that is south of Israel) was at least 175 kilometers, but could have been as much as 300 kilometers. Joel repeats the motto of Amos: "The Lord also will roar out of Zion, and utter his voice from Jerusalem," and adds the seismic theophany imagery "the heavens and the earth shall shake" (

Joel repeats the motto of Amos: "The Lord also will roar out of Zion, and utter his voice from Jerusalem," and adds the seismic theophany imagery "the heavens and the earth shall shake" (